Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The Intervention

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a frequently used model of counseling. CBT is based on two foundational principles: a) our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are related, and b) by changing any one of these, we can produce change in the others. CBT is a combination of two schools of therapy: cognitive therapy and behavior therapy. Cognitive therapy focuses on modifying maladaptive or unhelpful thoughts as the primary way to change behavior and improve student functioning, whereas behavior therapy focuses on changing patterns of reinforcement and punishment as the primary way to change behavior and improve student functioning. CBT combines these two schools of thought and takes principles from both. From the CBT perspective, some of the problems that students experience are, in part, due to unhelpful patterns of thoughts and behavior that they learn over time. We can help students who are struggling by helping them use effective coping skills and new or helpful ways of thinking and behaving.

Who Can Provide This Intervention?

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can only be provided by mental health professionals with training in CBT. There are many training programs and courses you can take to become competent in CBT if this is not a treatment that was emphasized in your training. Although you should not practice CBT if you are not trained in it, there are many principles of CBT that may be useful to help you formulate your intervention plan for your student(s). These principles and skills may be useful for both individual and group sessions.

Basic Principles

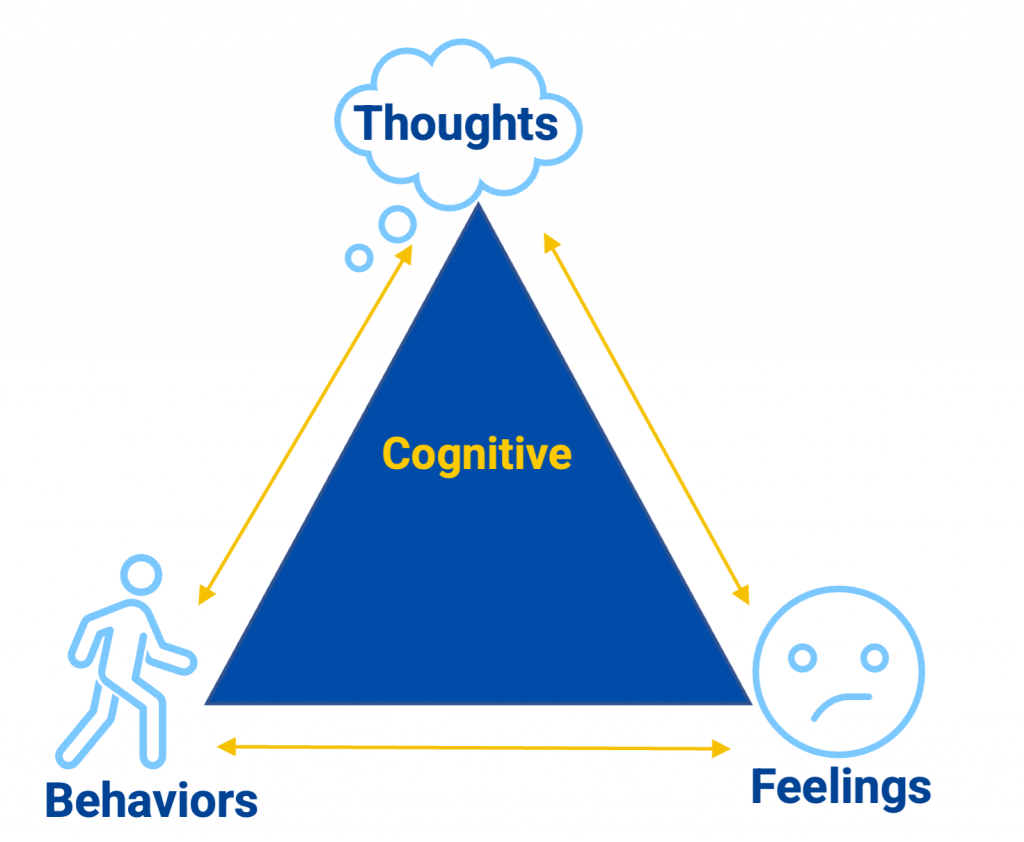

The CBT Triangle

The CBT Triangle is a visual depiction of the main principles of CBT. Our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors all reciprocally impact one another. For example, imagine you have a student who comes to you with anxiety about taking tests. A thought that they may have is: I am going to fail my test. This thought about failing their test may lead to physical feelings of anxiety, like heart racing or sweating. Their behavioral response may be to avoid studying for the test, or to cry when presented with the test. Using CBT, we can target any one of these points on the triangle to begin to address the problem.

- For example, we might target the maladaptive thought of “I am going to fail my test” by learning to question that thought, explore evidence for it, challenge the thought, and replace it with something that is more adaptive (If I study for this test, I will probably pass it). Over time, changing this thought to a more helpful one can help to reduce the physical feelings of anxiety, and promote behaviors that are likely to lead to success.

- Alternatively, or in addition, we can target the feelings of anxiety (racing heart, sweating) by teaching the student effective coping skills that regulate the flight or flight system, such as deep breathing or progressive muscle relaxation. Some forms of mindfulness counseling can achieve these goals. Over time, changing these physical sensations can reduce the physical feelings of anxiety and promote behaviors that are likely to lead to success (studying, taking the test).

- We could also target their behavior directly through the use of gradual exposure techniques such as systematic desensitization. The counselor helps the student develop a hierarchy of fears related to test taking and then works with the student to engage in exposure tasks. The student is exposed to the feared situation and coached to use the learned coping techniques (breathing, relaxation, cognitive reframing) long enough for the body’s fight or flight system to habituate. After repeated exposures, the body is “retrained” to not react to the feared situation. Reducing the body’s physiological reactivity reduces emotional discomfort and avoidance which allows the student to engage in studying or test taking more successfully.

- As the student learns that they have some control over thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, they often gain a sense of self-efficacy or mastery that leads to increased use of the above coping skills and increases in helpful cognitions about the anxiety provoking situation (I can handle situations like this).

Automatic Thoughts

Automatic thoughts are the types of thoughts that go through our minds without any awareness. They often begin with or include the word, “I”. These are the thoughts that happen during situations or when we are thinking about events. Because these types of thoughts are rapid and automatic, it is difficult to evaluate how rational they are in the moment. Cognitive therapy techniques can be used to help students become aware of these thoughts and how they may be affecting their emotions and behaviors. Once aware of automatic thoughts, cognitive therapy techniques can be used to modify them.

Cognitive Errors

Automatic thoughts can lead us to make “cognitive errors”. These are errors that may lead us to intense negative emotions and/or maladaptive behaviors (e.g., avoidance, isolation). There are many common cognitive errors, some of which are listed below:

- Selective abstraction (mental filter, ignoring the evidence)

- When we draw a conclusion about a situation after only paying attention to a small portion of the information that is available about the given situation. Individuals may focus on a small piece of negative information while ignoring all of the positive pieces of information.

- Example: “A student got a lot of positive feedback on their presentation in class, but all they can think about is the one word they stumbled over”

- Arbitrary Inference (jumping to conclusions, mind reading, fortune telling)

- When an individual makes an interpretation of an event or situation without any factual evidence that would support this interpretation or in the face of contradictory evidence to their conclusion

- Example: “My friend didn’t respond to my text so he must be mad at me.”

- Overgeneralizing

- When an individual generalizes the outcomes of a situation based on an isolated event.

- Example 1: “I got a bad grade on my math homework”

- Example 2: “I am terrible at math and am never going to pass a math class”

- Catastrophizing and Minimizing

- The importance of an event is exaggerated or minimized.

- Example 1 (catastrophizing): “What if I mess up my audition and I don’t make the musical and everyone makes fun of me for the rest of the year?”

- Example 2 (minimizing): “It was just luck that I scored a goal in my soccer game”

- Personalizing (taking it too personally)

- When an individual believes that external events are related to themself and takes responsibility or blame for negative situations when there is no logical reason for the blame.

- Example: “They are jumping me in line just to make me mad”

- All-or-Nothing Thinking (black and white thinking)

- When an individual makes conclusions about themselves or others on the extremes of categories (e.g. all good or all bad, a failure or a complete success).

- Example 1: “I got a B on my assignment and now I am a failure at school because I always get As”

- Example 2: “If she says “no” (to coming to my party) she must hate me”

Schemas

Schemas are the basic structures or templates that we create in our minds to help us develop rules for processing and organizing information and guiding behavior. In general, schemas are adaptive because they help us to manage the large amount of information that we gather on a day-to-day basis and make decisions based on this information. Schemas can greatly influence an individual’s self-esteem and behavior. In CBT, we try to help clients identify and increase their helpful schemas while changing or unlearning our unhelpful schemas. Unhelpful or maladaptive schemas may include things like, I am stupid, I need to be perfect for others to accept me, I can’t ever be comfortable around other people, or I am unlovable.

Useful CBT Exercises

Thought Record

A thought record is an exercise commonly used as an early step in CBT to help clients learn to identify their automatic thoughts. Being able to identify these thoughts and the associated feelings are an important first step in later being able the challenge these thoughts. Download the “CBT Thought Record Example” below for an example and template you can use with students.

Steps for Implementing

- Provide or draw three columns on a piece of paper that include labels of “Event”, “Automatic Thoughts” and “Emotions”

- Have your student think about a recent situation that happened that makes them feel strong emotions like anxiety, anger, sadness, or happiness.

- Have your student imagine themselves in that situation and think about how they felt while it was happening. Have them consider the thoughts that may have been going through their mind.

- Write this event, the automatic thoughts, and the emotions in the column on the thought record. This can be difficult for young children and many adolescents. Automatic thoughts are not descriptions of what happened, but statements about oneself and reflect one’s beliefs and values.

- Once you practice this with your student, this can be something that they do for homework and bring back to your next session to discuss.

Examining Evidence for Automatic Thoughts

Once a student becomes proficient at identifying their automatic thoughts, it is important to teach them to critically examine these thoughts to see if they are true or logical. For each automatic thought, have your student make a list of all of the evidence for this automatic thought. Then they should create a list of all of the evidence against this automatic thought. Once these lists are created, they can use them to identify and examine the cognitive errors that they are making with automatic thought and brainstorm alternative thoughts that are more helpful and more accurately reflect the reality of the event. When doing this, it is important to take a curious and collaborative stance (let’s be detectives to see if any of these thoughts might be unhelpful and if so, identify an alternative more helpful thought) and to ask questions with curiosity rather than as if there is a right or wrong answer (explore and discover together). As the you discuss these, you can help the student learn the name for the cognitive mistake and normalize how common it is.

Download the “CBT Examining the Evidence Example” below for an example and template you can use with students. This table of examining the evidence is just one of the many ways you can begin to challenge their unhelpful thoughts. You can also think about “what is the worst that could happen?” or thinking about potential cognitive errors that you may be making. There are multiple approaches you can take, and you may need to see what works best for your student.

Materials

Intervention Scorecard

This intervention is recommended for the following presenting problems.

Select an age group:

Recommended| Presenting Problem | Effectiveness | Magnitude | Effort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Other suitable presenting problems